At the heart of Dr. Tom Chau’s work is one simple idea: every child has something to say. That’s why he’s daring to open up a world of communication, freedom and independence for kids with disabilities.

“There’s this whole notion that communication has to be with words,” Dr. Chau says. “But in many ways, communication is actually limited by words.”

He points to the quiet understanding between a parent and child in a hospital room, the grip of a hand, a glance, a presence.

“There is communication that’s happening right there that is so rich, so powerful, and probably more meaningful than any word you could ever articulate.”

Dare to pay attention

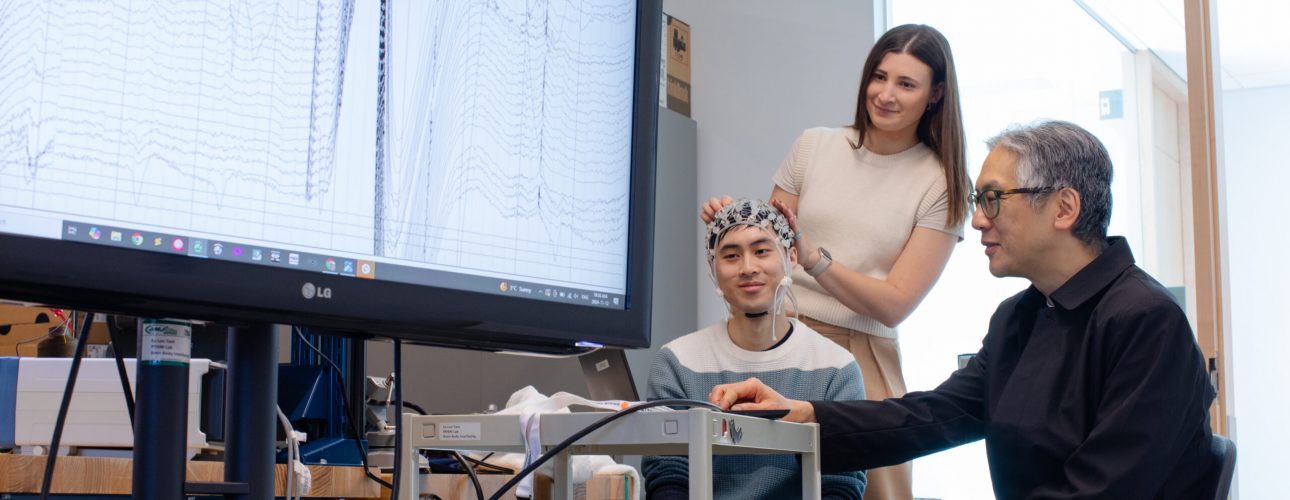

Dr. Chau leads the PRISM Lab at Bloorview Research Institute, located inside Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. Through such cutting-edge technology as the lab’s brain computer interface (BCI), kids with limited speech and movement use the power of their brains to do everyday kid things, like play a song, paint, use a bubble machine, move a wheelchair and communicate.

This kind of bold, innovative work is at the heart of Holland Bloorview’s $100-million Together We Dare campaign. As Canada’s hospital for patients with disabilities, Holland Bloorview is daring everyone to think differently, to challenge what they think they know and to show up for kids with disabilities everywhere.

One of those kids is 18-year-old Nathaniel. Diagnosed with cerebral palsy at a young age, he’s been part of the Holland Bloorview community for most of his life, taking part in everything from therapy and recreation programs to specialized clinics.

Two years ago, he began using BCI. While he hasn’t yet used it to select words or sentences, the technology is already opening new doors.

“He gets excited using it,” says his mom, Tanya. “He makes art with it. He plays games. He chooses what he wants to do, and that alone is huge.”

For Nathaniel, who is non-verbal and faces certain physical challenges, even something as simple as choosing can be difficult. Traditional switches didn’t always work. Smiling to activate a device was impossible on days when he didn’t feel well. But with BCI, it’s different.

“It means the world,” says Tanya. “It helps him participate in decisions about his care, his day, his life.”

Dare to stop looking away

Even with BCI, the path to connection isn’t always smooth. The technology can cost more than $1,000 and isn’t yet covered through Ontario’s Assistive Devices Program. And while the tools are powerful, they’re not perfect.

“Communication needs to be available 24/7, and we’re not there yet,” Dr. Chau says. “That’s a gap I’d love to see us close.”

Yet some of the toughest barriers aren’t technological at all. They’re human. True communication requires patience. It means slowing down, sitting with silence and resisting the urge to speak for someone else.

That belief is also shaping the next chapter of research at the PRISM Lab. One area of focus is brain synchrony, when brain activity between people aligns during shared moments, like playing music or simply being together.

Now Dr. Chau’s team is exploring how to visualize that connection or even turn it into sound. They’re also developing BCI tools for kids with cortical vision impairments—where the brain has trouble processing what the eyes see—by using touch and sound instead of visuals.

Dare to catch up

Because of silos in healthcare, it can take 17 years for research to translate to care. That’s why Holland Bloorview is daring to mobilize innovative research and collaboration faster than ever before, so kids with disabilities can get the care they need when they need it.

Since 2019, the research-integrated clinics at Holland Bloorview have been using BCI technology. Today over 200 kids access the clinic, combining the power of research and clinical care. Holland Bloorview is also helping other centres across Ontario launch BCI programs so more kids can ride bikes, play games and show the world who they are.

As for Dr. Chau, daring is more than a campaign theme: it’s a call to action.

“We need to dare to go beyond what our senses tell us when we first meet a child with disabilities. They have needs, preferences, hopes and dreams just like anyone else,” he says.

“We have to give space for those things to be expressed, learned and celebrated.”